[caption id="attachment_1448" align="aligncenter" width="940"] Lifeguards from the Spanish NGO Proactiva Open Arms aboard the former fishing trawler Golf Azzurro watch the C Star vessel run by a group of anti-immigration activists in the Western Mediterranean Sea August 15, 2017. REUTERS/Yannis Behrakis[/caption]

The refugee crisis that has been unfolding before our eyes in the past few years might soon come to a halt in the Mediterranean region – the Italian government has taken controversial steps in order to stem the flow of migrants into the country, by drafting a code of conduct for NGOs (non-governmental organisations) that operated in the Mediterranean Sea under the pretext of “rescue operations”. This move comes after the recent public outcry in the Italian media regarding the legality of the operations that these NGOs are involved in, with many accusing them with charges of international smuggling and human trafficking.

The 11-point code of conduct, that includes proposed new rules that will ban making phone calls or firing flares that might signal human traffickers that they could push their boats out to sea, is expected to be followed by all NGOs, with refusal of the terms risking denial of access to Italian ports for the humanitarian vessels altogether. Some other new rules are: the NGOs will be obliged to let police travel with them during their operations; the boats will no longer be allowed to transfer refugees to other bigger ships; total prohibition of operating in sovereign Libyan waters; turning off the on-board transponders (wireless communication devices); turning on lights to make their presence at sea obvious to anyone in the area; declaring the sources of their funding.

The 11-point plan has already been presented to nine NGOs that operate in the Mediterranean Sea – five out of those nine, including

Doctors Without Borders,

Sea Watch,

SOS MEDITERRANEE,

Sea Eye,

Jugend Rettet, the

Lifeboat Foundation and the

Boat Refugee Foundation, refused to sign it. Only three –

Save the Children,

MOAS (Migrant Offshore Aid Station) and

Proactiva Open Arms – accepted to strictly abide by the code.

[caption id="attachment_1449" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

TO GO WITH AFP STORY BY FANNY CARRIER - (FILES) This file photo taken on November 5, 2016 shows members of Maltese NGO MOAS helping people to board a small rescue boat during a rescue operation of migrants and refugees by the Topaz Responder ship run by Moas and the Red Cross, on November 5, 2016 off the coast of Libya. / AFP PHOTO / ANDREAS SOLARO[/caption]

Critics of the plan have already said that the Italian proposals could have a disastrous impact on the NGO missions and that the attempts to restrict the search and rescue operations could risk the endangering of thousands and thousands of lives. Nonetheless, the small flotilla that the NGOs operate in the Mediterranean Sea is responsible for over 40% of new migrant arrivals in Italy – better put together, a third of all migrants brought ashore this year, according to the Italian coastguard.

In order to see the bigger picture, first we must look at the numbers – in all, more than 600.000 migrants from sub-Sahara Africa have reached Italy over the past four years, with tens of thousands more expected in the coming months. 85.217 migrants have come to Italy so far this year, up 8.9% compared with the same period in 2016 (according to data released by the Italian interior ministry). This huge number of arrivals has taken its toll on the Italian authorities and public, with many clashes occurring between the latter and the migrants. Accommodation is also a huge issue, with thousands of newcomers living in central train stations or temporary housing granted by the authorities. It’s no wonder that under these conditions, the crime statistics have gone up and the public demands some kind of action.

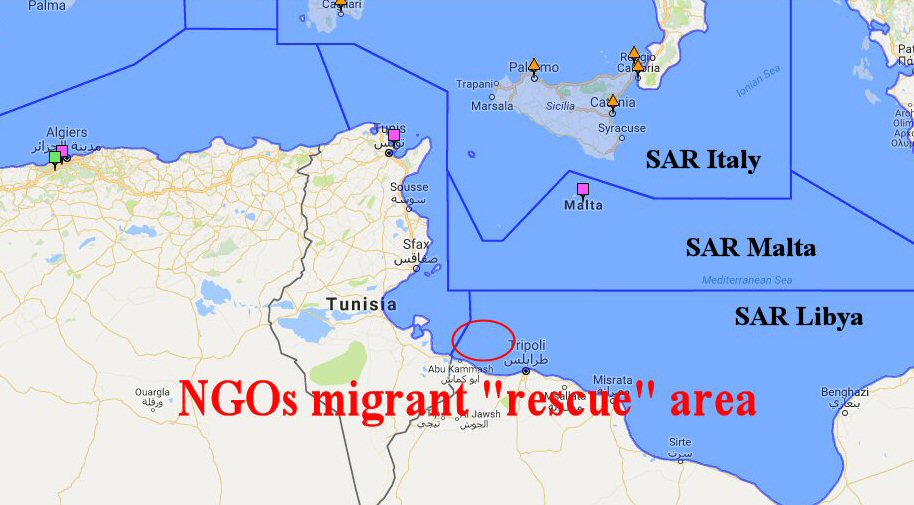

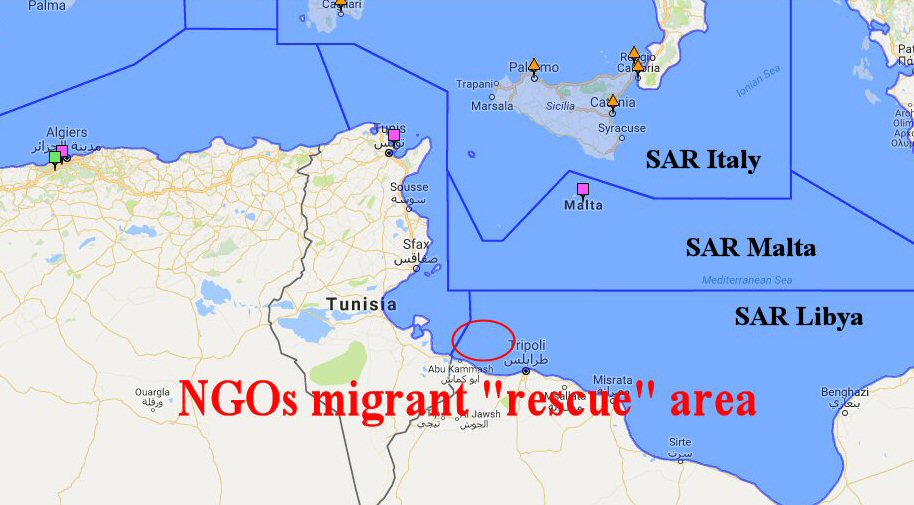

The Italian government is rightfully viewing these NGOs with increasing suspicion – especially when the other European countries have done virtually nothing to help the Italians in the last few months. Rome suspects that the presence of the NGOs just outside Libyan territorial waters encourages human traffickers to operate in that region. The NGOs have denied these allegations, saying that thousands of refugees would die in their way over to the Italian coastline.

Nearly all migrants that have arrived in Italy are young men from West Africa – most if not all of them paid a ticked to the smugglers boat, ticket that ranges from 1500-2000 euro/migrant. If we add up all the tickets in a single year, we reach the staggering sum of 300 million euros in ticket sales/year. Moreover, when looking at the situation from the perspective of the NGOs – that the justification for the presence of the aid-agency fleets in the Southern Mediterranean is to save lives – nothing really makes sense. If the fleets did not patrol whatsoever, there would be far fewer deaths, mainly because there would be far fewer smugglers at sea, hence far fewer migrants as well. If this lucrative business of smuggling would not be empowered by these NGOs, the people behind this large-scale human trafficking operation would stop altogether – after all, why risk passing the entire Mediterranean Sea for a couple thousands of dollars, if the probable outcome is the prospect of drowning?

The truth is definitely somewhere in the middle, but the fact of the matter is that most NGOs portray their operations as search-and-rescue missions in the Mediterranean Sea, while they really conduct their business one kilometer away from the Libyan coastline. Matter that begs to ask the question – are these NGOs hand-in-hand with the human traffickers or are they legitimately trying to help other people? Regardless of the answer, sadly, the outcome is the same – the ones empowered by all of this are the smugglers themselves, who are getting richer and richer at the expense of the suffering of others.

Libya has also made the decision to bar foreign vessels from a stretch of water off its coast – move that surprisingly coincided with the decisions made by the

Save the Children and

Sea Eye NGOs to suspend operations in that area “in response to the Libyan move”. Libya’s navy has ordered all foreign vessels to stay out of a coastal “search and rescue zone” and issued several statements against the non-governmental organisations, accusing them of facilitating illegal migration. Libyan Brigadier Qassem said for CNN: “

We are capable of conducting rescue work. Our presence cancels their presence. We are fed up with these organizations. They increased the number of immigrants and empowered smugglers. Meanwhile, they criticize us for not respecting human rights”.

Libya’s move has definitely payed off – in the first 10 days of August, the number of migrants making the crossing to Italian shores dropped by 76% compared to the same period last year. This pattern has been displayed in July as well, when the Italian authorities measured a significant drop in arrivals. What happened in July? That’s when the code of conduct was first reported on and that’s when the Italian authorities started their cooperation with the Libyan authorities.

As we can see, there’s always a solution to be found, as long as there is a will behind it. No one is against legal immigration, that’s not the point here. Everyone should be able to move from one country to another, as long as the correct legal measures are taken and as long as the person is vetted accordingly by the authorities. Illegal immigration benefits only the smugglers – while the countless people involved suffer and die, at the hands of injustice and incompetence.

TO GO WITH AFP STORY BY FANNY CARRIER - (FILES) This file photo taken on November 5, 2016 shows members of Maltese NGO MOAS helping people to board a small rescue boat during a rescue operation of migrants and refugees by the Topaz Responder ship run by Moas and the Red Cross, on November 5, 2016 off the coast of Libya. / AFP PHOTO / ANDREAS SOLARO[/caption]

Critics of the plan have already said that the Italian proposals could have a disastrous impact on the NGO missions and that the attempts to restrict the search and rescue operations could risk the endangering of thousands and thousands of lives. Nonetheless, the small flotilla that the NGOs operate in the Mediterranean Sea is responsible for over 40% of new migrant arrivals in Italy – better put together, a third of all migrants brought ashore this year, according to the Italian coastguard.

In order to see the bigger picture, first we must look at the numbers – in all, more than 600.000 migrants from sub-Sahara Africa have reached Italy over the past four years, with tens of thousands more expected in the coming months. 85.217 migrants have come to Italy so far this year, up 8.9% compared with the same period in 2016 (according to data released by the Italian interior ministry). This huge number of arrivals has taken its toll on the Italian authorities and public, with many clashes occurring between the latter and the migrants. Accommodation is also a huge issue, with thousands of newcomers living in central train stations or temporary housing granted by the authorities. It’s no wonder that under these conditions, the crime statistics have gone up and the public demands some kind of action.

The Italian government is rightfully viewing these NGOs with increasing suspicion – especially when the other European countries have done virtually nothing to help the Italians in the last few months. Rome suspects that the presence of the NGOs just outside Libyan territorial waters encourages human traffickers to operate in that region. The NGOs have denied these allegations, saying that thousands of refugees would die in their way over to the Italian coastline.

Nearly all migrants that have arrived in Italy are young men from West Africa – most if not all of them paid a ticked to the smugglers boat, ticket that ranges from 1500-2000 euro/migrant. If we add up all the tickets in a single year, we reach the staggering sum of 300 million euros in ticket sales/year. Moreover, when looking at the situation from the perspective of the NGOs – that the justification for the presence of the aid-agency fleets in the Southern Mediterranean is to save lives – nothing really makes sense. If the fleets did not patrol whatsoever, there would be far fewer deaths, mainly because there would be far fewer smugglers at sea, hence far fewer migrants as well. If this lucrative business of smuggling would not be empowered by these NGOs, the people behind this large-scale human trafficking operation would stop altogether – after all, why risk passing the entire Mediterranean Sea for a couple thousands of dollars, if the probable outcome is the prospect of drowning?

TO GO WITH AFP STORY BY FANNY CARRIER - (FILES) This file photo taken on November 5, 2016 shows members of Maltese NGO MOAS helping people to board a small rescue boat during a rescue operation of migrants and refugees by the Topaz Responder ship run by Moas and the Red Cross, on November 5, 2016 off the coast of Libya. / AFP PHOTO / ANDREAS SOLARO[/caption]

Critics of the plan have already said that the Italian proposals could have a disastrous impact on the NGO missions and that the attempts to restrict the search and rescue operations could risk the endangering of thousands and thousands of lives. Nonetheless, the small flotilla that the NGOs operate in the Mediterranean Sea is responsible for over 40% of new migrant arrivals in Italy – better put together, a third of all migrants brought ashore this year, according to the Italian coastguard.

In order to see the bigger picture, first we must look at the numbers – in all, more than 600.000 migrants from sub-Sahara Africa have reached Italy over the past four years, with tens of thousands more expected in the coming months. 85.217 migrants have come to Italy so far this year, up 8.9% compared with the same period in 2016 (according to data released by the Italian interior ministry). This huge number of arrivals has taken its toll on the Italian authorities and public, with many clashes occurring between the latter and the migrants. Accommodation is also a huge issue, with thousands of newcomers living in central train stations or temporary housing granted by the authorities. It’s no wonder that under these conditions, the crime statistics have gone up and the public demands some kind of action.

The Italian government is rightfully viewing these NGOs with increasing suspicion – especially when the other European countries have done virtually nothing to help the Italians in the last few months. Rome suspects that the presence of the NGOs just outside Libyan territorial waters encourages human traffickers to operate in that region. The NGOs have denied these allegations, saying that thousands of refugees would die in their way over to the Italian coastline.

Nearly all migrants that have arrived in Italy are young men from West Africa – most if not all of them paid a ticked to the smugglers boat, ticket that ranges from 1500-2000 euro/migrant. If we add up all the tickets in a single year, we reach the staggering sum of 300 million euros in ticket sales/year. Moreover, when looking at the situation from the perspective of the NGOs – that the justification for the presence of the aid-agency fleets in the Southern Mediterranean is to save lives – nothing really makes sense. If the fleets did not patrol whatsoever, there would be far fewer deaths, mainly because there would be far fewer smugglers at sea, hence far fewer migrants as well. If this lucrative business of smuggling would not be empowered by these NGOs, the people behind this large-scale human trafficking operation would stop altogether – after all, why risk passing the entire Mediterranean Sea for a couple thousands of dollars, if the probable outcome is the prospect of drowning?

The truth is definitely somewhere in the middle, but the fact of the matter is that most NGOs portray their operations as search-and-rescue missions in the Mediterranean Sea, while they really conduct their business one kilometer away from the Libyan coastline. Matter that begs to ask the question – are these NGOs hand-in-hand with the human traffickers or are they legitimately trying to help other people? Regardless of the answer, sadly, the outcome is the same – the ones empowered by all of this are the smugglers themselves, who are getting richer and richer at the expense of the suffering of others.

Libya has also made the decision to bar foreign vessels from a stretch of water off its coast – move that surprisingly coincided with the decisions made by the Save the Children and Sea Eye NGOs to suspend operations in that area “in response to the Libyan move”. Libya’s navy has ordered all foreign vessels to stay out of a coastal “search and rescue zone” and issued several statements against the non-governmental organisations, accusing them of facilitating illegal migration. Libyan Brigadier Qassem said for CNN: “We are capable of conducting rescue work. Our presence cancels their presence. We are fed up with these organizations. They increased the number of immigrants and empowered smugglers. Meanwhile, they criticize us for not respecting human rights”.

Libya’s move has definitely payed off – in the first 10 days of August, the number of migrants making the crossing to Italian shores dropped by 76% compared to the same period last year. This pattern has been displayed in July as well, when the Italian authorities measured a significant drop in arrivals. What happened in July? That’s when the code of conduct was first reported on and that’s when the Italian authorities started their cooperation with the Libyan authorities.

The truth is definitely somewhere in the middle, but the fact of the matter is that most NGOs portray their operations as search-and-rescue missions in the Mediterranean Sea, while they really conduct their business one kilometer away from the Libyan coastline. Matter that begs to ask the question – are these NGOs hand-in-hand with the human traffickers or are they legitimately trying to help other people? Regardless of the answer, sadly, the outcome is the same – the ones empowered by all of this are the smugglers themselves, who are getting richer and richer at the expense of the suffering of others.

Libya has also made the decision to bar foreign vessels from a stretch of water off its coast – move that surprisingly coincided with the decisions made by the Save the Children and Sea Eye NGOs to suspend operations in that area “in response to the Libyan move”. Libya’s navy has ordered all foreign vessels to stay out of a coastal “search and rescue zone” and issued several statements against the non-governmental organisations, accusing them of facilitating illegal migration. Libyan Brigadier Qassem said for CNN: “We are capable of conducting rescue work. Our presence cancels their presence. We are fed up with these organizations. They increased the number of immigrants and empowered smugglers. Meanwhile, they criticize us for not respecting human rights”.

Libya’s move has definitely payed off – in the first 10 days of August, the number of migrants making the crossing to Italian shores dropped by 76% compared to the same period last year. This pattern has been displayed in July as well, when the Italian authorities measured a significant drop in arrivals. What happened in July? That’s when the code of conduct was first reported on and that’s when the Italian authorities started their cooperation with the Libyan authorities.

As we can see, there’s always a solution to be found, as long as there is a will behind it. No one is against legal immigration, that’s not the point here. Everyone should be able to move from one country to another, as long as the correct legal measures are taken and as long as the person is vetted accordingly by the authorities. Illegal immigration benefits only the smugglers – while the countless people involved suffer and die, at the hands of injustice and incompetence.

As we can see, there’s always a solution to be found, as long as there is a will behind it. No one is against legal immigration, that’s not the point here. Everyone should be able to move from one country to another, as long as the correct legal measures are taken and as long as the person is vetted accordingly by the authorities. Illegal immigration benefits only the smugglers – while the countless people involved suffer and die, at the hands of injustice and incompetence.

Trackbacks and Pingbacks